Flying-foxes

Flying-foxes are nomadic mammals that travel across large areas of Australia, feeding on native blossoms and fruits, spreading seeds and pollinating native plants.

Flying-foxes (also known as fruit bats) are the largest members of the bat family.

Flying-foxes feed mainly at night on nectar, pollen and fruit and will also feed on flowering and fruiting plants in gardens and orchards.

They are vital to the health and regeneration of Australian native forests because they can transport pollen over vast distances and are also able to disperse larger seeds.

What do they look like and where do they live?

There are 3 species of flying-fox native to New South Wales.

The black flying-fox (Pteropus alecto) is almost completely black in colour with only a slight rusty red-coloured collar and a light frosting of silvery grey on its belly. They have an average weight of 710 grams and are one of the largest bat species in the world. Their wingspan can be more than 1 metre.

The black flying-fox (Pteropus alecto) is almost completely black in colour with only a slight rusty red-coloured collar and a light frosting of silvery grey on its belly. They have an average weight of 710 grams and are one of the largest bat species in the world. Their wingspan can be more than 1 metre.

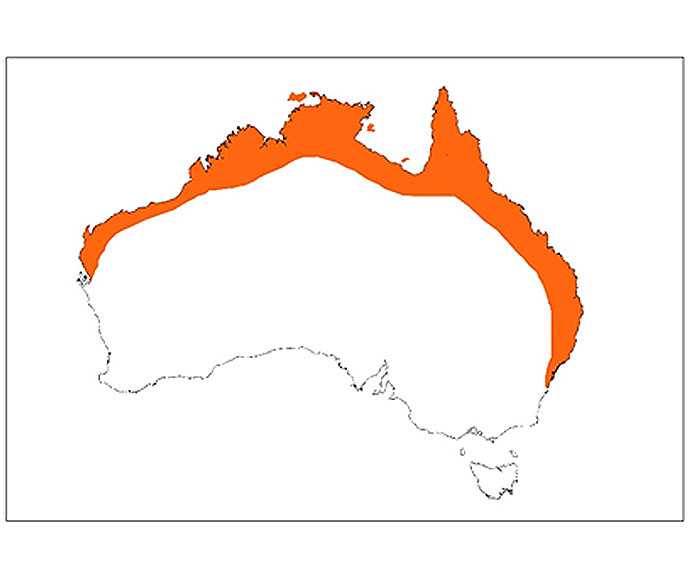

The black flying-fox is common to the coastal and near coastal areas of northern Australia from Shark Bay in Western Australia to Lismore in New South Wales. It is also found in New Guinea and Indonesia.

Distribution

The grey-headed flying-fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) is easily recognisable by its rusty reddish-coloured collar, grey head and hairy legs. Adults have an average wingspan up to 1 metre and can weigh up to 1 kilogram. It is also the most vulnerable species because it competes with humans for prime coastal habitat along the south-east Queensland, NSW and Victorian coasts.

The grey-headed flying-fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) is easily recognisable by its rusty reddish-coloured collar, grey head and hairy legs. Adults have an average wingspan up to 1 metre and can weigh up to 1 kilogram. It is also the most vulnerable species because it competes with humans for prime coastal habitat along the south-east Queensland, NSW and Victorian coasts.

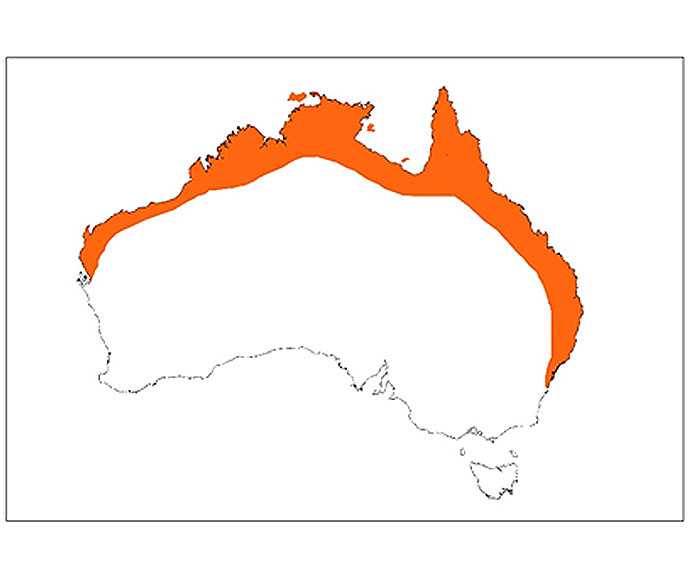

Traditional grey-headed flying-fox habitat is located within 200km of the eastern coast of Australia, from Bundaberg in Queensland to Melbourne in Victoria. In 2010, many grey-headed flying-foxes were found roosting and foraging outside these traditional areas; some were found as far inland as Orange and as far south-west as Adelaide.

Distribution

The little red flying-fox (Pteropus scapulatus) with a weight of 300–600 grams is the smallest Australian flying-fox and has reddish brown-coloured fur. Little reds will often fly much further inland than other flying-foxes.

The little red flying-fox (Pteropus scapulatus) with a weight of 300–600 grams is the smallest Australian flying-fox and has reddish brown-coloured fur. Little reds will often fly much further inland than other flying-foxes.

Little-red flying-foxes are the most widespread species of megabat in Australia. They occupy a broad range of habitats found in northern and eastern Australia including Queensland, Northern Territory, Western Australia, New South Wales and Victoria.

Distribution

Flying-fox camps

A flying-fox camp is a patch of trees that flying-foxes are found in during the day. Being social animals, they congregate in these camps to roost, find a mate and feed their young.

Flying-fox mothers typically give birth to one baby every year. Newborns are entirely dependent on their mothers in the first few months of life. They cling to her when she flies out from camp to feed at night. After a few weeks, mothers leave their young overnight in the camps while they go out to feed.

Some characteristics of camps are very common:

- they tend to be greater than one hectare in size

- they are usually near water

- the ground is relatively level

- trees are usually greater than five metres tall.

However, these characteristics also describe many areas of vegetation across the flying-fox range where they don’t roost. It’s not clear why flying-foxes choose the sites they do.

Some flying-fox camps are permanently occupied. Even after most of the animals have moved elsewhere, a few animals will stay.

The numbers of flying-foxes at camps fluctuate with the food supply. They may be occupied and then vacant every year, or they may only be occupied every few years when seasonal conditions mean food is available.

Other camps are transient. These are most likely to form during landscape-wide food shortages where the flying-foxes need to break into small groups and form camps close to limited food supplies. All camps tend to be self-organised, only supporting as many animals as the local food supply can support. As soon as the food supply dwindles, they move to a new site.

Flying-foxes are not faithful to camps. The same animal may return to the same camp each year, but they may not. They can move from one camp to another and back again over a few days.

Flying-foxes in urban areas

Flying-foxes are increasingly moving into urban areas. This may be a response to changing environmental conditions such as the loss of previous camps and foraging areas due to clearing for housing, agriculture or forestry. It may also be a response to local food shortages or fewer predators in urban areas.

The urbanisation of flying-foxes has increasingly brought flying-foxes into contact with people. It may look as though they are becoming more abundant, but recent estimates of the vulnerable grey-headed flying-fox show no evidence of any increase in their population.

Living near a flying-fox camp can be difficult for many people and there are some strategies that may help.

Visit Living near a flying-fox camp for more information.

Issues with flying-foxes in urban areas can also be addressed by managing the flying-fox camps and effective communication.

Visit Flying-fox camp management for more information.

Flying-fox movements

Flying-foxes are highly mobile animals. Each species found in NSW is treated as a single population throughout their entire distribution range. A single grey-headed flying-fox may move from Bundaberg in Queensland to Melbourne in Victoria over a few months.

Flying-fox movements are generally in response to food availability, rather than any strict seasonal migratory patterns. They also do not move as a uniform group. Individual flying-foxes intermix independently throughout their range.

Flowering and fruiting in native forests and rainforests attract flying-foxes. In Australian forests, flowering and fruit production occurs sporadically, attracting flying-foxes when the food is there. As flying-foxes move across their range, they can use short stop-overs to rest and forage before moving to their destination camp.

When environmental conditions are right, food supplies may suddenly become abundant in certain areas. These natural events can attract a large number of flying-foxes, resulting in an influx of animals to areas that may not have attracted such large numbers before.

We don’t know exactly how flying-foxes know where food supplies will be, especially when these are in areas that are hundreds of kilometres away. It is also not known how they organise themselves to congregate in numbers according to how much food is available.

We do know that even if there are large numbers of flying-foxes one year, they may not be there the following year. If food supplies are more consistent, the arrival and departure of flying-foxes may be more predictable.

Flying-foxes can travel up to 50 km from their camps to feed at night. They leave the camps at dusk and return at dawn.

Current information suggests that the decision about which camp to return to is based on the proximity and quality of nearby food supplies. This helps the flying-fox to conserve energy and make the most of available food.

If there is not much food available, or if it is of low quality, they will tend to roost closer to the food resource. They may establish several smaller camps rather than one large camp. It is common to see many smaller camps in new locations during times of food shortages.

You may hear flying-foxes feeding noisily in your garden. This will only last if the food is available. If they are causing a significant disturbance, you can remove the food supply (e.g. remove the fruit from the tree, or use wildlife-friendly netting) and the flying-foxes will look for food somewhere else.

Health and handling

Human infections with viruses borne by flying-foxes are very rare. There is no risk of infection if you do not make physical contact with a flying-fox. There are no reports of people contracting diseases from living close to flying-fox camps.

For more information visit Health and handling

The black flying-fox (Pteropus alecto) is almost completely black in colour with only a slight rusty red-coloured collar and a light frosting of silvery grey on its belly. They have an average weight of 710 grams and are one of the largest bat species in the world. Their wingspan can be more than 1 metre.

The black flying-fox (Pteropus alecto) is almost completely black in colour with only a slight rusty red-coloured collar and a light frosting of silvery grey on its belly. They have an average weight of 710 grams and are one of the largest bat species in the world. Their wingspan can be more than 1 metre.

The grey-headed flying-fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) is easily recognisable by its rusty reddish-coloured collar, grey head and hairy legs. Adults have an average wingspan up to 1 metre and can weigh up to 1 kilogram. It is also the most vulnerable species because it competes with humans for prime coastal habitat along the south-east Queensland, NSW and Victorian coasts.

The grey-headed flying-fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) is easily recognisable by its rusty reddish-coloured collar, grey head and hairy legs. Adults have an average wingspan up to 1 metre and can weigh up to 1 kilogram. It is also the most vulnerable species because it competes with humans for prime coastal habitat along the south-east Queensland, NSW and Victorian coasts.

The little red flying-fox (Pteropus scapulatus) with a weight of 300–600 grams is the smallest Australian flying-fox and has reddish brown-coloured fur. Little reds will often fly much further inland than other flying-foxes.

The little red flying-fox (Pteropus scapulatus) with a weight of 300–600 grams is the smallest Australian flying-fox and has reddish brown-coloured fur. Little reds will often fly much further inland than other flying-foxes.