New South Wales has a huge diversity of incredible plants, animals and ecosystems, collectively known as ‘biodiversity’.

New South Wales has a huge diversity of incredible plants, animals and ecosystems, collectively known as ‘biodiversity’.

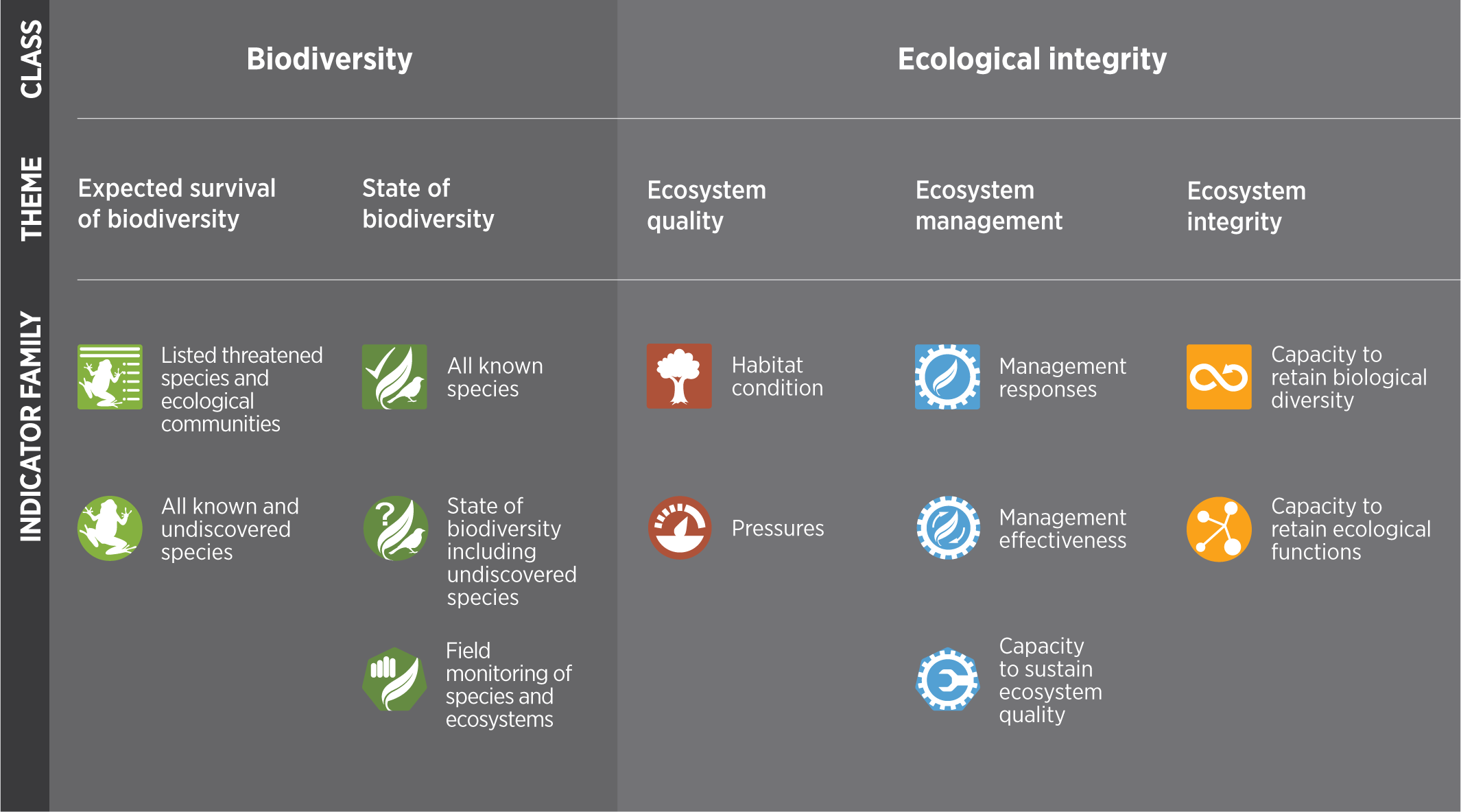

High biodiversity indicates a healthy ecosystem. Understanding the status of biodiversity, and how it’s changing, is important to be able to protect and manage it into the future.

The challenge

We need to manage and protect our biodiversity. To do this, policymakers, business owners and communities all need relevant and accurate measures so they can make good decisions and direct resources appropriately.

To feed into policy and legislative requirements, such as reporting under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016, our scientists look at:

- at risk ecosystems and species

- locations that need the most management, such as key habitat areas or more likely to be disturbed

- actions that could be taken to protect or rehabilitate

- whether conservation efforts are working.