Natural rainfall and dam spills achieved a range of ecological outcomes in the Border Rivers system in 2022–23.

Key outcomes

Under wet to very wet conditions, significant flows in the catchment met environmental demands, resulting in:

- continuous connection to the Barwon River for the whole year

- multiple flow events in the Boomi River across a range of flow categories, including small and large freshes, bankfull and overbank events

- inundation of large areas of the floodplain

- summer flows in Morella Watercourse.

Catchment conditions

During 2022–23, weather patterns in the Border Rivers region were driven by various climate conditions including a strong La Niña event. This resulted in high rainfall and moderate temperatures, with significant flows throughout the system as major dams reached and exceeded storage capacity.

Higher than average flows and significant floodplain inundation occurred through the catchment, meeting instream and floodplain environmental demands and negating the need to deliver water for the environment throughout the water year.

About the catchment

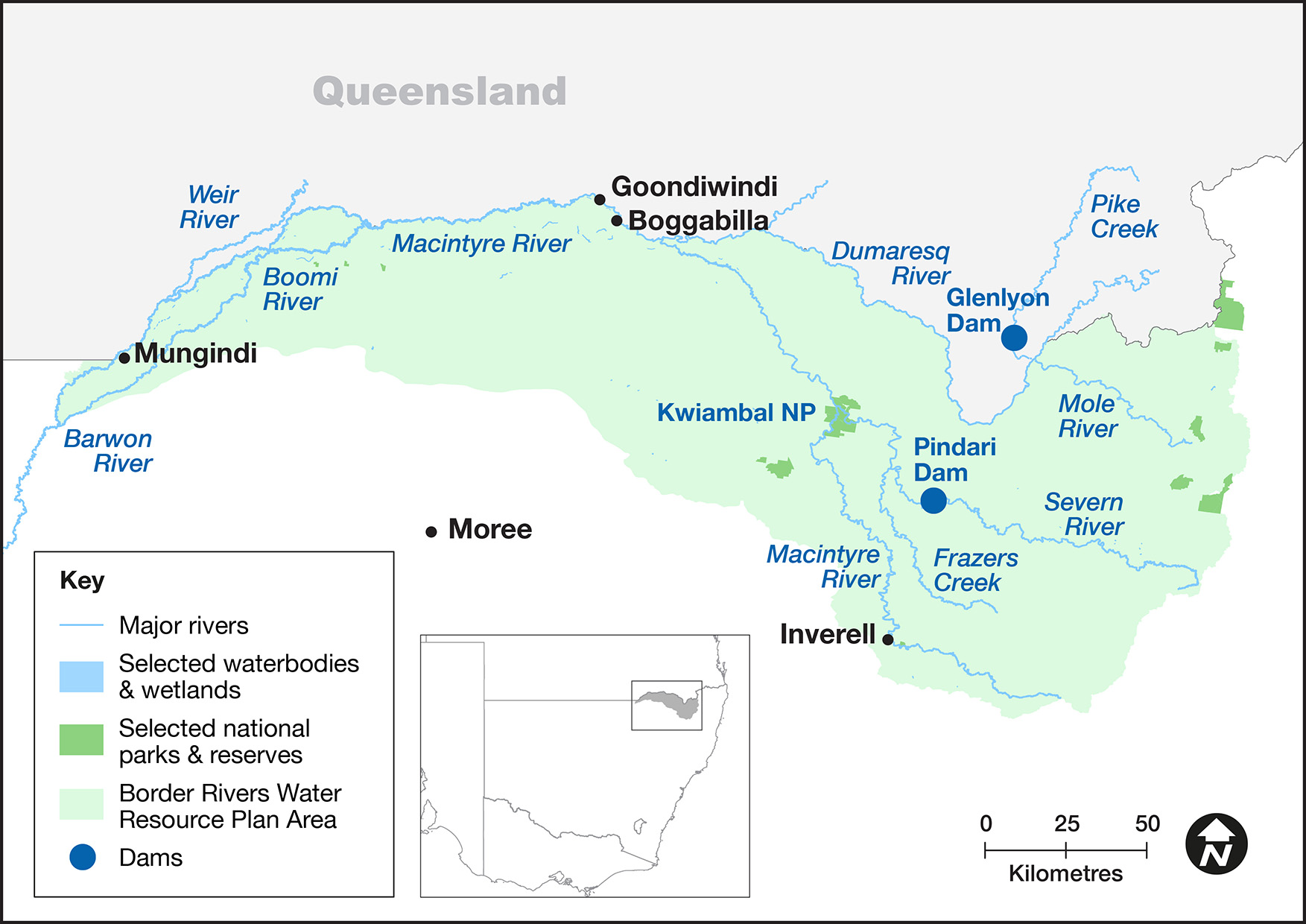

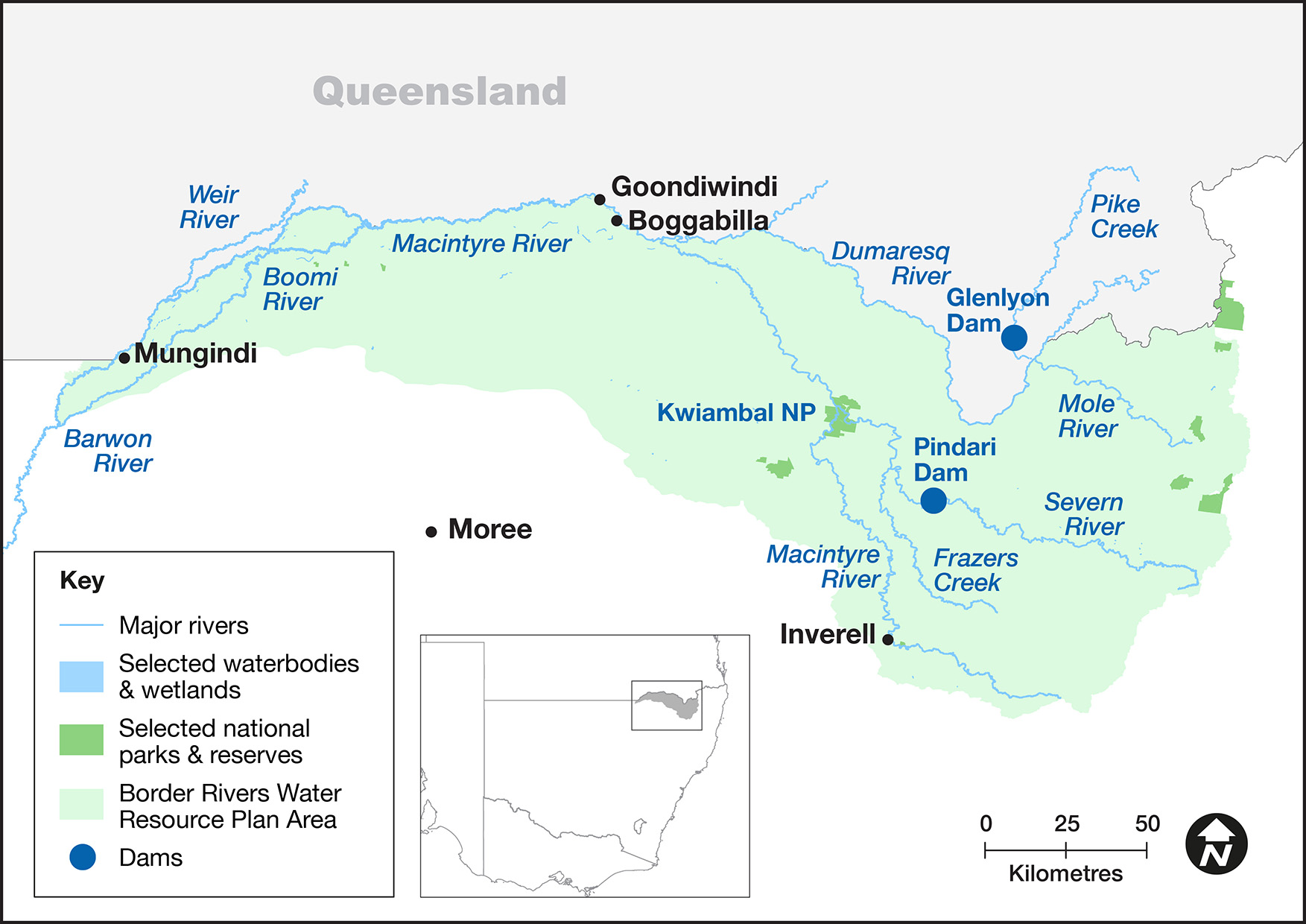

The Border Rivers catchment hugs the NSW–Queensland border in north-east NSW and covers an area of 24,000 square kilometres. Located in a temperate and sub-tropical climatic zone, rainfall is typically summer dominant with an annual average rainfall of 620 millimetres at Goondiwindi.

The major tributaries of the catchment are the Macintyre, Severn, Dumaresq and Weir rivers and Macintyre Brook, becoming the Barwon River near Mungindi. The Border Rivers catchment has 2 major water storages – the Pindari Dam on the Severn River in NSW, and Glenlyon Dam on Pike Creek in Queensland.

The Morella Watercourse, including Boobera and Pungbougal lagoons, are located on the Macintyre River floodplain and are important cultural sites for Aboriginal people. These wetlands are also listed as wetlands of national significance.

Water for Country

The Border Rivers catchment is Country to the Bigambul, Euahlayi, Githabul, Kambuwal, Gamilaraay/Gomeroi/Kamilaroi, Kwiambul, and Ngarabal Aboriginal peoples.

Water for Country is environmental water use planned by the Department of Planning and Environment \and Aboriginal people to achieve shared benefits for the environment and cultural places, values and/ or interests. In the 2022–23 water year in the Border Rivers catchment, environmental water managers did not deliver water for the environment due to significant rainfall, flows and dam spills.

Boobera Lagoon is situated to the south-west of Goondiwindi on the Macintyre River floodplain along Morella Watercourse. The lagoon (along with others on this watercourse) has significant Aboriginal heritage value. The Gamilaraay (Kamilaroi) people believe Boobera Lagoon is the resting place of Garriya (rainbow serpent). The site is estimated to contain millions of stone artefacts as well as scar and canoe trees.

The floodplain around Boobera Lagoon observed significant rainfall and flows through October 2022. The Morella Watercourse, including Boobera Lagoon, was connected to the wider Macintyre floodplain around some of these high flow events, with the largest occurring in late October. Water dried off the floodplain through November, with isolated areas remaining into early December.