Welcome to our first Saving our Species update

Find out more about projects and research to save threatened plants and animals in NSW.

Discover the conservation work being done by scientists, land managers, representatives from community groups and government agencies, business partners and volunteers.

Do you have a story to share? Email savingourspecies@environment.nsw.gov.au

Saving the southern corroboree frog

Actions are under way in the Snowy Mountains to save the southern corroboree frog from extinction.

To help save the southern corroboree frog Pseudophryne corroboree from extinction, quarantined breeding enclosures have been established in Kosciuszko National Park under Saving our Species.

The southern corroboree frog is one of Australia’s most endangered species, and is found only in the high altitude wetlands and bogs of Kosciuszko National Park. Surveys and monitoring suggest that fewer than 20 adults remain in the wild, compared with hundreds of thousands in the 1980s.

Numbers have declined as a result of a pathogen known as the Amphibian Chytrid Fungus. This lethal disease, which cannot be cured, has led to the decline and extinction of many frog species worldwide.

OEH staff designed and constructed the enclosures to:

In April last year, some captively-bred southern corroboree frogs and their eggs were released into the first quarantined enclosure. One year on, the adult frogs have bred and remain in good condition. More captive-bred eggs have been released recently into a second field enclosure.

The project is a collaboration between OEH, Taronga Zoo, the Amphibian Research Centre, Melbourne Zoo and Healesville Sanctuary and is being keenly watched by those involved in frog conservation worldwide.

See the story: 'In the spotlight: Michael McFadden' below for more information on breeding threatened frogs in captivity at Taronga Zoo.

read more

Conserving Floyd's grass and the black grass-dart butterfly

By Mick Andren, Office of Environment and Heritage

Rehabilitation work in northern NSW is benefiting two threatened species: Floyd’s grass and the butterfly that depends on it, the black grass-dart.

The habitat of Floyd’s grass Alexfloydia repens is highly specialised (low-lying swamp forest) and subject to weed invasion. It is also sparsely distributed, restricted to the north coast of NSW. Mick Andren and Mark Cameron from OEH investigated its distribution in 2009 and mapped 293 tiny patches, only a few of which are in a national park.

To eradicate the weeds that threaten the long-term survival of Floyd’s grass and the dependent black grass-dart butterfly Ocybadistes knightorum, skilled bush regenerators from Coffs Coast Bush Regeneration group were enlisted under Saving our Species. The regenerators used delicate hand weeding and wick-wiping to remove the highly invasive broad-leaved paspalum from Bongil Bongil National Park.

Botanist Peter Richards monitored the outcomes of weed removal and found that Floyd’s grass grew rapidly and luxuriantly in the formerly weed-infested areas.

Coffs Harbour Regional Landcare, Coffs Harbour City Council and the Gumbaynggirr Aboriginal community (in the Aboriginal-owned Gaagal Wanggaan National Park) have also contributed to the project.

Due to its position in the landscape, sea-level rise poses another serious threat to the grass, so the next challenge is to identify suitable adaptation strategies for its long-term survival.

read more

Innovative monitoring methods accurately record threatened microbat populations

By Doug Mills, Office of Environment and Heritage

OEH monitoring techniques have enabled scientists to accurately record annual populations of eastern bentwing-bats.

The eastern bentwing-bat Miniopterus schreibersii is a small (~15 grams) microbat that feeds exclusively on insects such as moths and beetles. It is distributed along the eastern seaboard of Australia from Cape York, Queensland to Castlemaine in Victoria and is listed as vulnerable under the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995.

Every summer, female bentwing-bats congregate in a few caves in Wee Jasper and Bungonia in southern NSW to give birth and raise their young. Each cave can be inhabited by tens of thousands of bats, creating difficulties in accurately estimating numbers.

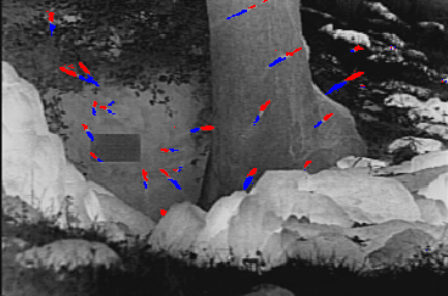

OEH staff have developed a monitoring program using thermal infra-red video and tracking and counting software, so population numbers can now be counted accurately and quickly. Several surveys can be undertaken throughout the breeding season.

Because the technique has proven to be extremely accurate, population trends can be identified from year-to-year. Excitingly, at one of the caves, the population has been increasing by about 10% a year over the last three years.

Also through the monitoring program, spring and autumn migrations to and from the maternity cave have been timed. This information has helped to:

OEH is sharing the methodology with scientists in South Australia, helping them to monitor the critically endangered southern bentwing-bat.

read more

Regent honeyeater: a survival plan

By Dean Ingerswen, BirdLife Australia

Thanks to recovery actions by BirdLife Australia and Taronga Zoo, the critically endangered regent honeyeater has a better survival plan.

BirdLife Australia and Taronga Zoo have been engaged under Saving our Species to secure the critically endangered regent honeyeater Xanthomyza phrygia. There are thought to be as few as 400 mature birds left in the wild. The three-year recovery project includes:

-

protecting key parcels of regent honeyeater habitat on private land and managing the impacts of noisy miners on key sites

-

supplementing the wild population by releasing captive-bred birds

-

monitoring and banding wild regent honeyeaters

-

maintaining a captive-bred population at Taronga Zoo.

Monitoring sites in the Capertee and Lower Hunter valleys have been identified. Recent sightings in the Capertee Valley were evaluated but no birds could be caught and banded. In the Lower Hunter Valley, the condition of the spotted gum-ironbark habitat favoured by the species was evaluated.

The collaboration between BirdLife Australia and the Nature Conservation Trust to establish covenants on private land is under way. Negotiations are being conducted with landholders.

Over the next 12–18 months, facilities for captive breeding and release will be upgraded at Taronga Zoo. As recently released birds have bred in the wild, the focus is on maintaining and enhancing breeding facilities.

It is hoped that these measures, along with the high ongoing community support, will improve the conservation status of regent honeyeaters.

read more

Learning more about threatened shorebirds in Botany Bay

Volunteers regularly count an amazing array of shorebirds next door to Sydney’s busiest airport.

Right next door to Australia’s busiest airport, NSW Waders Study Group volunteers have been regularly counting an amazing range of local and migratory shorebirds to determine long-term population trends since 2001. Under Saving our Species, Botany Bay has been identified as an important habitat for the shorebirds, as it is a breeding area for the threatened migratory little tern and resident pied oystercatcher.

The volunteer program provides invaluable data for shared wildlife databases such as Birdlife Australia’s Birddata Atlas and helps OEH to identify important roosting sites and actions needed to lessen the impacts of human and predator threats on these vulnerable birds.

It is important that they get the space to feed and roost, especially as some of the migratory birds travel more than 11,000 km non-stop on only 300 grams of fat.

read more

Why the pale imperial hairstreak butterfly needs brigalow woodland

Results from a research program to find out where in NSW the pale imperial hairstreak butterfly lives, its habitat requirements and the threats it faces are now in.

The pale imperial hairstreak butterfly Jalmenus eubulus or brigalow butterfly lives in brigalow woodland Acacia harpophylla, mostly in south-east Queensland. Until recently it was known only from a single record in northern NSW south of Boggabilla and was subsequently classified as critically endangered in NSW.

To find out more about its possible distribution in NSW and the threats it faces, surveys for the butterfly were undertaken in 2013 during March, when the butterflies are most active. Surveys were conducted on patches of brigalow woodland near the location of the original record.

Brigalow woodland, itself an endangered ecological community, has been extensively cleared and is highly fragmented, reducing suitable habitat for the butterfly. Most habitat occurs in small patches on private land, travelling stock reserves or roadsides.

The caterpillars of the pale imperial hairstreak butterfly only eat brigalow leaves. The caterpillars are also looked after by several species of ant. As a result, caterpillars tend to occur on plants with foliage close to the ground which are easily accessible by the ants.

The pale imperial hairstreak butterfly was found at four additional sites, highlighting the need to regularly monitor these sites and other areas of suitable habitat to help understand whether the population is increasing or decreasing.

It is imperative to maintain or improve the condition and extent of brigalow woodland for the butterfly.

read more

In the spotlight: Michael McFadden

Meet Michael McFadden, Unit Supervisor, Herpetofauna Division, Taronga Zoo and find out about the captive breeding of threatened frogs

Michael McFadden has been working on amphibian conservation programs at Taronga Zoo for nine years. His job includes:

-

maintaining healthy populations of threatened frog species through effective husbandry, breeding and genetic management

-

working with threatened species officers to implement recovery actions to help improve species’ conservation status.

‘One of my favourite parts of the job is to fine-tune the techniques to achieve successful and reliable breeding. Finding the right reproductive triggers can sometimes be challenging so it’s always a great feeling to see the egg clutches coming through,’ says Michael.

‘The husbandry and breeding of the frogs varies enormously between species. There are common features such as filtered water and a nutrient-loaded insect diet, but the enclosure set-up and breeding trigger vary quite a lot between species. For example, corroboree frogs need facilities to be cooled down to five degrees Celsius to match the winter climate of the Snowy Mountains and live on sphagnum moss without any standing water, while booroolong frogs can be maintained at a temperate winter climate and are kept in an enclosure with flowing water and large cobblestones to match their habitat.’

Michael’s current projects include:

-

working under Saving our Species with OEH and other organisations to reintroduce threatened southern and northern corroboree frogs, booroolong frogs, alpine tree frogs and green and golden bell frogs into the wild

-

researching why alpine tree frogs have an innate immunity, and booroolong frogs have an acquired immunity, to Amphibian Chytrid Fungus

-

researching artificial reproduction techniques for threatened frog species.

read more

The importance of private landholders

Private landholders play a vital role in conserving threatened species. A range of agreements provide even more options.

Private landholders play a vital role in threatened species conservation and many landholders are already managing part of their property for conservation.

Ways of protecting threatened species on private land include in-perpetuity conservation agreements and biobanking agreements with OEH and trust agreements with the Nature Conservation Trust. Other options include conservation property vegetation plans negotiated with Local Land Services, and wildlife refuges administered by OEH.

Landholders who prefer not to enter into agreements can take up property registration schemes such as Land for Wildlife or Wildlife Land Trust, which help them to manage parts of their property for conservation.

Of the more than 400 conservation projects for threatened species already established under Saving our Species, approximately 70 are located on private land permanently protected by either a conservation agreement, a trust agreement or a biobanking agreement. These projects help protect species like the red-lored whistler, Dorrigo daisy bush and southern brown bandicoot.

To find out more about protecting threatened species on private land, email savingourspecies@environment.nsw.gov.au.

read more