Bringing little penguins back to Eden

A small, feathered creature on the south coast has recently been given lots of attention, and for good reason.

On the far south coast of New South Wales, the small town of Eden had a little penguin breeding colony until the 1990s, when foxes and domestic dogs drove the population to extinction.

In 2015, the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water’s senior scientist Nicholas Carlile brought his seabird restoration expertise to the local area, collaborating with ranger Wendy Noble. They accessed money from community fundraising and Bega Shire Council and worked towards re-establishing a colony of little penguins using cutting edge techniques never seen before in Australia.

Love machine at Eagles Claw

Designing the perfect nest

‘I surveyed the site with a citizen scientist,’ said Nicholas. ‘While it didn’t have good penguin habitat, it was the perfect place to set up a fence, which is the key to keeping out foxes and dogs.’

The team designed and developed artificial nesting habitat, called Eden Burrows, made from concrete and perlite. The burrow is goanna-proof, designed to be too heavy for them to lift, with a tight curve to stop them entering the nesting chamber.

‘The designs went through several iterations,’ recalled Nicholas. ‘A Sydney group called the Fix-it-Sisters built them for us, and they’re now used in several places for habitat augmentation, including in Eden.’

Once the nesting burrows were in place, sounds of penguins mating and calling to each other were broadcast nightly from huge stadium speakers controlled by the ‘love machine’, a solar-powered sound device installed at the potential colony site.

‘We monitored the process with camera traps,’ Nicholas said. ‘We captured about 20 images of penguins in 2020, 70 images in 2021 and hundreds in 2022. It’s been a slow burn!’

Watching for new life

This year brought an exciting development: footage of penguins courting, mating, then building a nest out of grass in a hard-to-reach rocky outcrop was captured on camera.

‘In July, we saw lots of activity with 2 penguins passing in front of the camera carrying nesting material. In August, we started to see only a single bird, and we knew something was happening,’ said Nicholas. ‘Penguins alternate which parent incubates the egg each night so that both parents can have a break and go to sea to feed.’

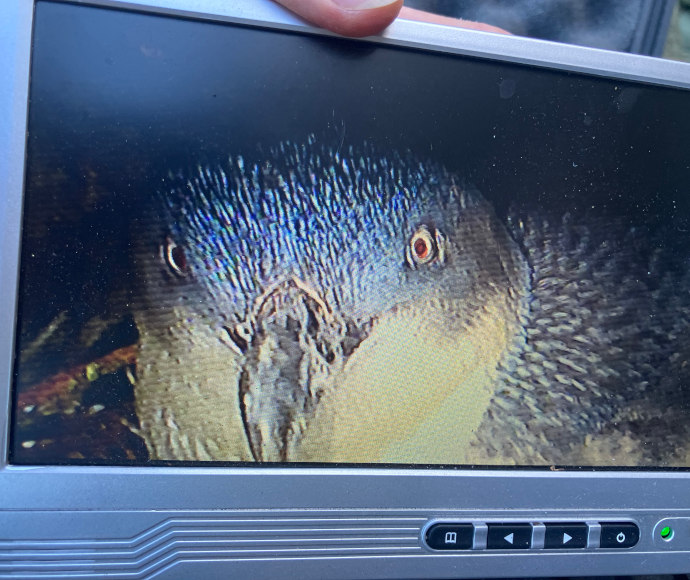

‘In early September I used a flexible burrow camera to monitor the nest,’ recalled Nicolas. ‘I could see the eggs and was able to remove the incubating bird.’

Courting little penguins hugging (Eudyptula minor)

Nicholas microchipped the penguin so the team could continue their monitoring. The fact that the penguin was not already chipped led the team to believe that they are likely part of a new nesting pair.

NSW National Parks and Wildlife ranger Wendy Noble confirmed that a single egg had hatched on Friday 6 October.

‘Wendy couldn’t see the chick, but we suspected it had hatched because it was too long for the penguin to still be sitting on the egg without anything happening,’ Nicholas said. ‘The other major clue it had hatched was that the adult was aggressive. They don’t behave this way unless they are defending a chick.’

When the chick fledges the nest at 8 weeks old, the parents will not teach them how to swim or fish. The return rate for penguin fledglings is not very high. ‘The parents don’t even teach them where home is,’ Nicholas said. ‘When the penguin chick gets in the water they will turn around and read the landscape to know where their home is. A third of them will get it right and turn up where they hatched if they return to land.’

Community support key for future success

After this year’s success, the team will continue to use the sound attraction system and cameras next breeding season.

‘We’re a few years away from a sufficient founding colony, which would be more than 5 pairs of birds,’ said Nicholas. ‘We hope that next year we can build on our initial pair and create a stronger colony.’

The team credit community support and strong science for the project’s initial success. In future, they hope to stream the penguins via live webcam and predict they may even attract tourists to the area.

Hope for the future

In January 2024, one of the penguin parents was sighted returning to shore for their ‘catastrophic moult’. This is an annual occurrence during which penguins drop roughly 10,000 feathers, and regrow any worn feathers, which ensures they remain waterproof. Seeing one of the parents return for moulting season is a positive sign that the site continues to provide a safe haven. Scientists and the community are hoping more penguins arrive for the next breeding season joining the pair and rebuilding Eden’s lost penguin colony.