Location

To be announced

About Bessie Jean Guthrie

Bessie Guthrie lived by a mantra imparted on her as a young girl by her Aunt Janet, 'Never iron men’s shirts, Bessie.' She was a woman with a rich and varied life, who found her calling in activism and advocacy. A radical free thinker and feminist, Bessie dedicated her life to women’s rights, supporting the establishment of the first women’s refuge and playing a key role in the reformation of the NSW welfare system.

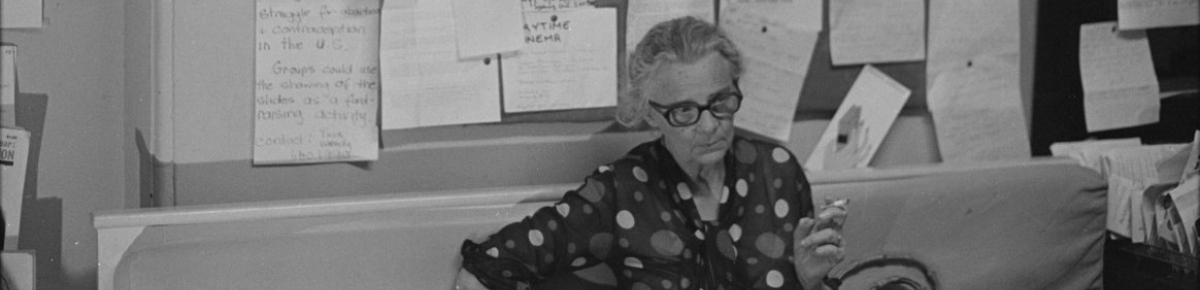

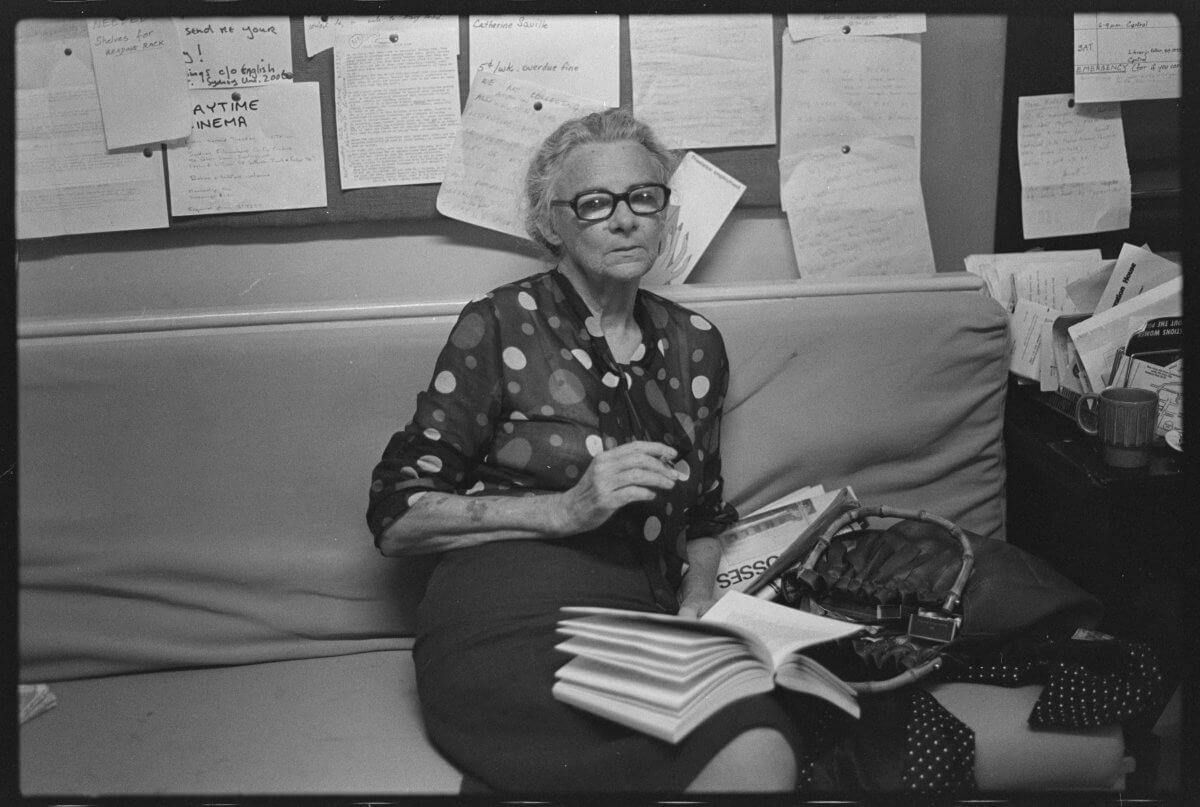

Bessie Guthrie at Sydney Women’s Liberation House, 1974

Education and early activism

Bessie Jean Thompson Guthrie (née Mitchell) was born in Glebe in 1905. She was raised and educated by her 2 aunts in a staunchly working-class, proto-feminist home. This upbringing fuelled her interest in the world and radical ideas (for the era) about women's role in society.

In 1921, Bessie began studying design at East Sydney Technical College, becoming the first woman to hold an exhibition of design art at that college. On graduating, she worked as a furniture draughtswoman with Grace Bros Ltd's department stores. She then opened a private interior design practice, selling the first design for modular furniture in Australia. However, as a proudly working-class woman she found the work ideologically challenging, stating in an interview, 'I didn't like interior decorating … because the women who could afford it were so uninteresting.'

She began frequently writing articles for Australian Women's Weekly, Australian Woman's Mirror and Good Fellows on how design could be used to improve the lives of women in poorer households. She later credited this era of her life with galvanising her leftist political sympathies as 'she realised to be successful in this industry, she would have to be a handmaiden to wealthier women, and she was not interested in that'.

As her interest in working for the wealthy waned, she embraced her love for writing and established the Viking Press in the late 1930s. She made a point of choosing to publish books that would otherwise be unlikely to be published – mainly contemporary poetry written by women.

However, with the outbreak of World War II and ensuing paper shortages, Bessie was forced to close the Viking Press. She was appointed head draughtswoman at De Havilland Aircraft Pty Ltd's experimental gliders factory before working in aircraft design for the Commonwealth government. When the war ended, Bessie took a role as a publicity officer with the feminist not-for-profit organisation Young Women's Christian Association. Her return to working for affluent women, along with seeing her fellow female wartime colleagues lose their jobs and freedoms as men resumed work, reignited a focus that lasted for the rest of her life – advocating for poor, young, lost women.

A lifelong pursuit

In 1950, Bessie married realist painter Clive Guthrie, who shared many of her political views. The couple settled in her family home in Glebe. Clive’s ill health led Bessie to take a stable job as a clerk in the Government Insurance Office of New South Wales.

During this time, Bessie began taking an interest in the children who would frequently enter their yard to snatch flowers and plants. One day she came face to face with one of the little girls, eventually inviting her into her home to talk. From that day forward, her home became a haven for victims of homelessness, domestic violence, abuse and alcohol dependency.

Bessie discovered the horrors of Parramatta Girls' Home and other similar state institutions through the relationship she built with several of the young girls she sheltered.

I've been waiting for you women to get here all my life.

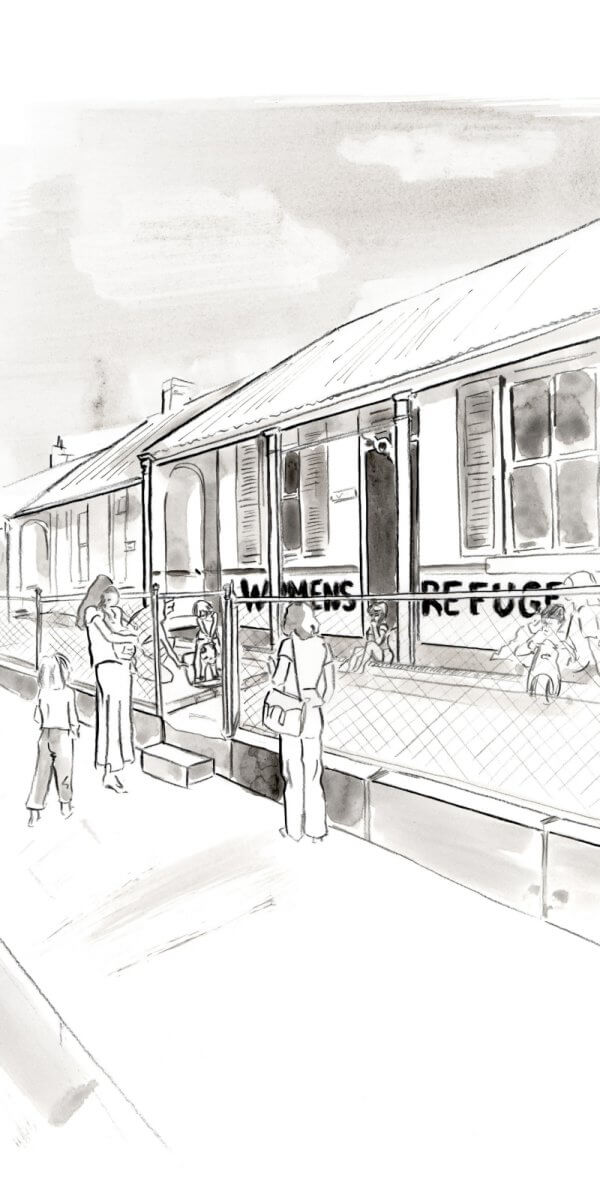

The Illustration Room, Elsie Refuge, artist’s impression, 2024

In 1970, Bessie walked into the office of the Women's Liberation Movement in Glebe. By then she already had decades of advocacy and activism under her belt. She greeted the other women with, 'I've been waiting for you women to get here all my life.'

Bessie saw the group as integral to bringing to light the issue of violence against women and improving social conditions for young women. In line with changing community attitudes towards feminism, the group progressed from producing publications and demonstrations to establishing support services.

In 1974, Bessie joined a small group of women who declared squatter's rights over 2 abandoned terraces in Glebe and established 'Elsie', the first refuge in Australia for women and children who were the victims of domestic violence. Within 6 weeks of opening, Elsie had sheltered 48 women and 35 children – proving its vital importance.

What started as a remarkable social experiment had profound consequences for hundreds of women in Sydney. The opening of Elsie Women’s Refuge set a precedent for nationwide action regarding services for women and children experiencing domestic violence.

The mark of a great person is making space for those behind them.

During this time with the Women's Liberation Movement, Bessie maintained her personal missions to raise awareness of the treatment of girls in state institutions, and advocate for changes to the 'exposure to moral danger' law. While the exact definition of the phrase varied, the result of the law was that children – mainly girls – were often declared 'uncontrollable', 'neglected' or 'exposed to moral danger' and deemed to be wards of the state, not because they had done anything wrong but because of the circumstances in which they found themselves. Indeed, most of the children and young women charged under this law were victims of abuse or poverty rather than offenders.

She continued to shelter women, all the while conducting research, amassing large quantities of evidence from the girls she sheltered detailing institutionalised abuse and arranging large-scale protests and demonstrations. It was one such protest outside Parramatta Girls' Home that caught the attention of ABC journalist Peter Manning. Working with Bessie, he reported an exposé on the abuse of girls in state care and the barbaric act of forced virginity testing.

Bessie passed in her home in Glebe in November 1977. Bessie’s campaigning had already led to the closure of Hay Institution for Girls in 1975 and the years that followed would also see the end of the compulsory virginity testing of girls charged by the Children's Court, the abolition of the charge of 'exposure to moral danger', reformation of the conditions in state-controlled child-welfare institutions and an increased emphasis on education for women and girls.

References

- ABC (28 October 2007) Creating a space: The life of Bessie Guthrie, Hindsight, ABC Radio National, Sydney.

- Bellamy S (1996) 'Bessie Jean Guthrie (1905–1977)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Australian National University website, accessed 16 June 2025.

- Dictionary of Sydney (n.d.) 'Sydney Women’s Liberation', Dictionary of Sydney, State Library of New South Wales website, accessed 16 June 2025.

- Dictionary of Sydney (n.d.) 'Women’s Liberation House', Dictionary of Sydney, State Library of New South Wales website, accessed 16 June 2025.

- Dwyer C (1 December 2021) 'Day 7: When Bessie Guthrie met the Women’s Liberation Movement', 16 Days Blogathon, accessed 28 July 2025.

- Gilchrist C (2015) 'Forty years of the Elsie Refuge for women and children', Dictionary of Sydney, State Library of New South Wales website, accessed 16 June 2025.

- McNicol E (20 March 2024) Squatting, kidnapping and collaboration: Australia's first women's shelters were acts of radical grassroots feminism, The Conversation website, accessed 10 June 2025.

- Trenoweth S (8 March 2024) Breaking boundaries: 50 years of Elsie, Australia's first women's refuge, The Australian Women's Weekly, accessed 10 June 2025.