Location

Grant Reserve (4B Neptune Street entry), Coogee NSW 2034

Sydney Coast is on land traditionally occupied by the Bidjigal, Birrabirragal and Gadigal people.

Accessibility

Wheelchair accessible

About Wilhelmina (Mina) Wylie

The sporting world has long been dominated by rivalries that have captivated audiences and made for history making clashes. However, 100 years before we had Serena versus Venus, Kobe versus LeBron or Thorpie versus Phelps, we had Mina versus Fanny.

Wilhelmina 'Mina' Wylie and Sarah ‘Fanny’ Durack were born in North Sydney just 2 years apart. Though they had radically different starts to their swimming careers, fate would bring them together and create a story for the ages. The pair overcame many hardships to become the first Australian women Olympic champions and the first women in the world to win Olympic medals in swimming. Their remarkable story highlights the strength and resilience of pioneering female athletes.

Mina is pictured next to her portrait in the Hall of Champions

Water baby

Born in 1891, Mina had swimming in her blood. Her father was a house painter turned long-distance plunging champion and, by just 5, she had joined him and her 2 brothers in a daring aquatic act where she swam underwater with her hands and feet tied together.

Her father quickly recognised her innate talents and began increasing the intensity of her training. However, rules restricting women from swimming in the presence of men in public pools remained limited Mina, so in 1907 her father built Coogee Baths (now Wylie’s Baths) to enable her to train with greater freedom.

It was here that Mina and Fanny Durack first crossed paths when Fanny began training at the baths. Over the following years, Mina and Fanny became close friends and training partners. Mina’s father encouraged them to innovate their swimming, working with them to perfect the stroke known as the ‘Australian Crawl’ (now known colloquially as freestyle).

Winner, winner

By the 1910–11 season, Mina was making big waves in the Australian swimming scene. That year Mina set a world record for the 100 yards freestyle at Rushcutters Bay Baths, beating the 5-year-old record held by Englishwoman Jenny Fletcher by 1.5 seconds. Over the season she went on to win against class fields over 50 yards, 100 yards and 440 yards. At the Australasian championships at Rose Bay, she bested Fanny Durack in the 100 yards breaststroke and the 100 yards and 200 yards freestyle.

Mina quickly rose to be one of the most dominant Australian swimmers of the era, racking up numerous national wins and unofficial world records. Had she been born a few years earlier, this may have been the pinnacle of her career; however, the announcement that the 1912 Stockholm Olympic games would feature the very first Olympic women’s swimming event provided Mina with the opportunity to make history representing her country on the world stage.

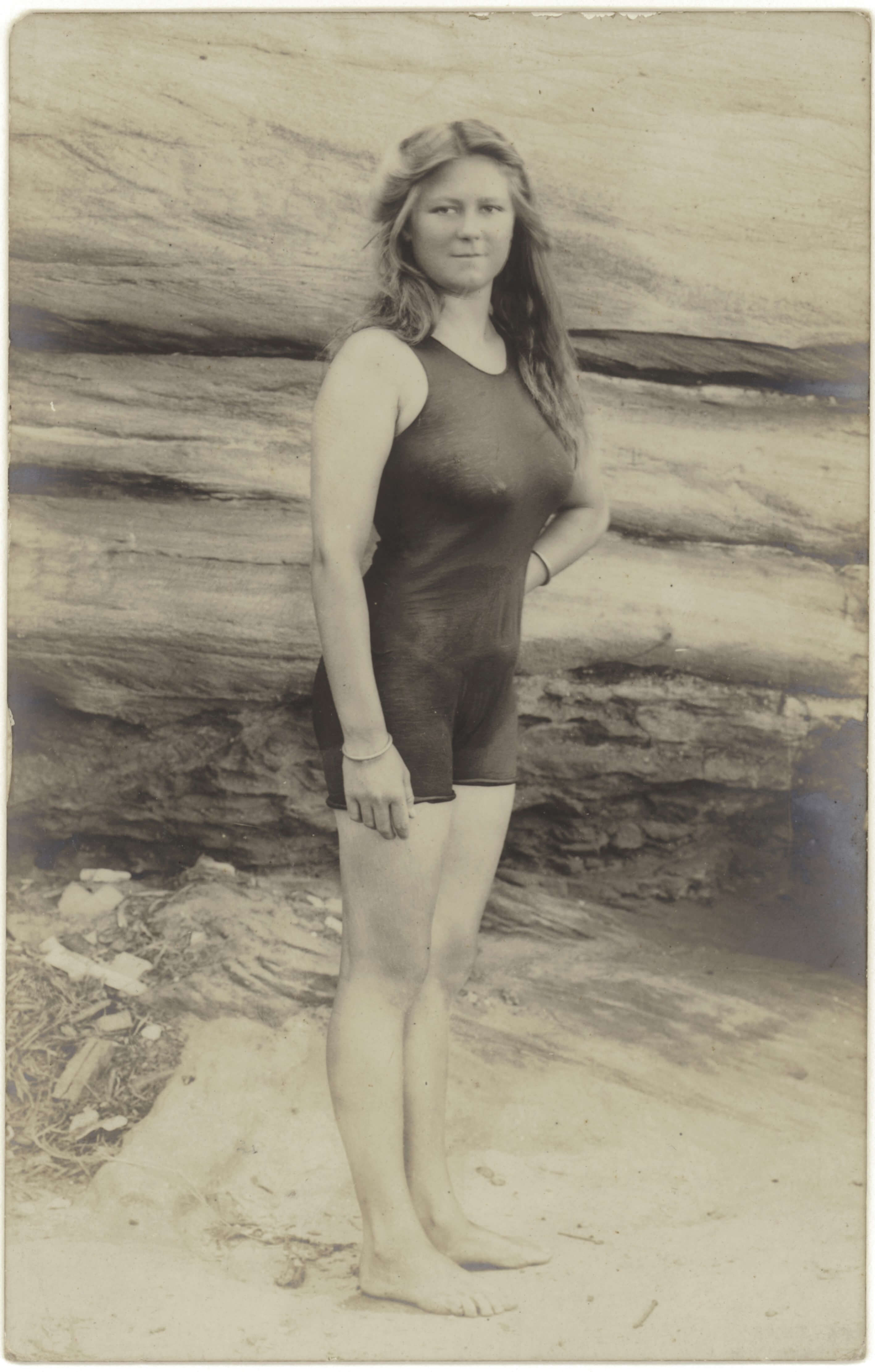

Wilhelmina (Mina) Wylie at the beach, 1910

Swimming against the tide

The first modern Olympic Games to feature female athletes was the 1900 Games in Paris. Each subsequent games, new women’s events were added, with swimming being perhaps one of the most controversial. Today, thousands of Sydneysiders flock to the beaches and public pools every day. However, in the early 1900s the increased interest in swimming clashed with ideas about ‘moral decency’. Many countries sought to uphold various restrictions, with Australian lawmakers imposing various laws such as a ban on men and women swimming together. While the laws were soon abandoned, mixed bathing remained a controversial subject.

Rose Scott, the President of the NSW Ladies' Amateur Swimming Association (which Fanny and Mina were both members of) firmly believed not only that men and women should not share a pool, but also that men should not watch women compete – as would be expected during the Olympics. Indeed, for the duration of their careers thus far, Mina and Fanny had only ever trained and competed in gender-segregated pools. While many did disagree with this position, the lack of support from their home representative body put Fanny and Mina’s Olympic campaign in jeopardy.

When the 1912 Olympic team was announced, Fanny's and Mina’s names were both absent. The Swimming Association said that this was because they could not afford to send female competitors. There was nationwide public outrage. Local and international publications ran stories urging the association to reconsider, and unsolicited donations from the public soon flooded in. Eventually the association relented, and Fanny and Mina formed the first Australian Olympic Ladies’ Swimming Team.

Portrait of Mina Wiley wearing her collection of winner’s badges, circa 1915

We are the champions

The women exceeded all expectations, both winning their heats and semi-finals and setting up an electric final. They even offered to swim 2 legs each so they could compete in the 4 x 100 m relay but were eventually refused permission. In the end, Fanny pipped Mina to take the 100 m freestyle gold, making them the first women in the world to win Olympic medals in swimming.

Fanny and Mina arrived back to Australia as heroes and carried that momentum through for several more years. While the cancellation of the 1916 Olympics due to World War I prevented them from defending their Olympic titles, they continued their successes.

By the time Mina retired in 1934, she had amassed 115 titles, including every Australian and NSW championship event in 1911, 1922 and 1924 in freestyle, backstroke and breaststroke.

A lasting legacy

Mina became one of the first female sporting celebrities, travelling to Europe and the USA to participate in various swimming carnivals. In 1975, she was selected as an honouree to the International Swimming Hall of Fame. In an unfortunate parallel to her 1912 Olympic campaign, Mina’s request to the federal government for expenses to attend the induction ceremony was denied, which again resulted in a nationwide fundraising campaign to cover her expenses.

Post-retirement, both Mina and Fanny dedicated themselves to coaching the next generation of swimmers, with Wylie teaching swimming at Presbyterian Ladies’ College, Pymble, from 1928 to 1970. The pair, who remained close friends for the remainder of their lives, are remembered as national heroines. They were instrumental in changing attitudes towards women’s sport and paved the way for the host of champion Australian women swimmers to follow.

At the Paris 2024 Olympics, 112 years after Fanny and Mina’s Olympic debut, women claimed 6 out of Australia’s 7 gold medals for swimming.

References

- Australian Women's Archives Project (2007) Fanny Durack, She’s Game – Women making Australian sporting history website, accessed 8 July 2025.

- EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum (20 March 2021) Fanny Durack – winner of the first women’s Olympic swimming medal, Europeana website, accessed 8 July 2025.

- National Library of Australia (30 July 2024) Fanny Durack, NLA website, accessed 8 July 2025.

- State Heritage Inventory (n.d.) Wylie’s Baths, Heritage NSW website, accessed 8 July 2025.